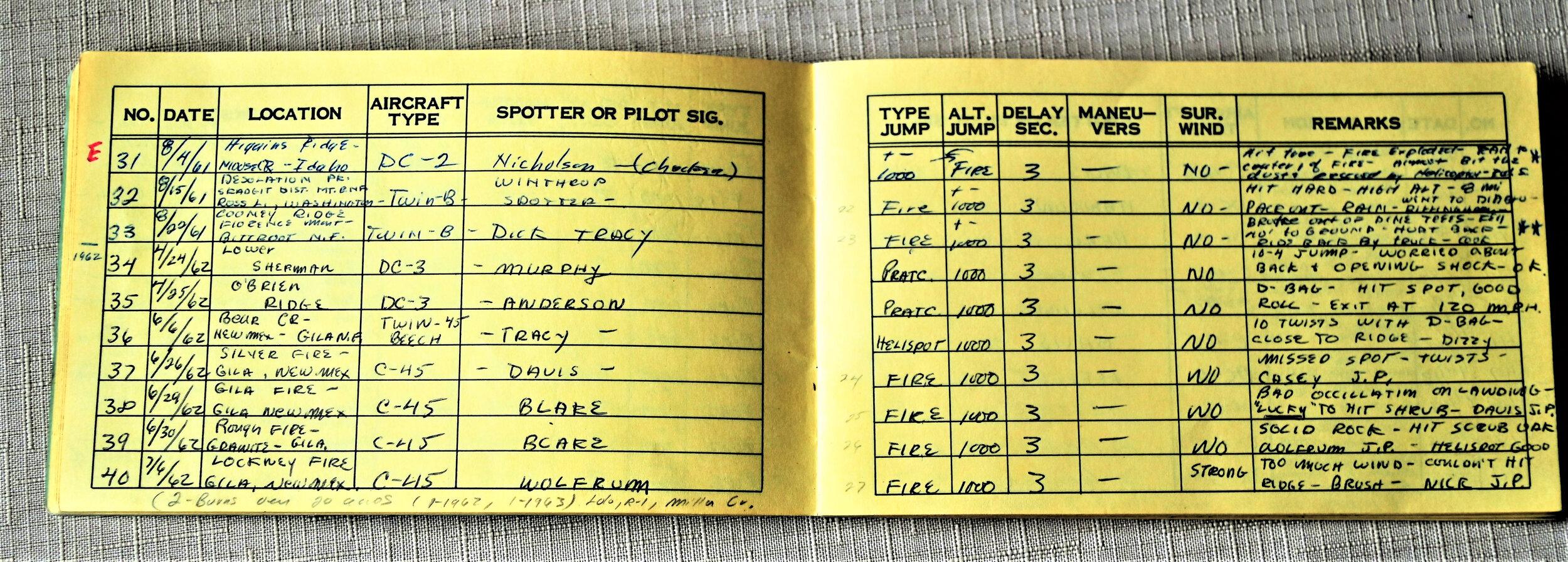

Higgins Ridge Fire, 1961

A Smokejumper’s Harrowing Tale

Written by Cyd Hoefle

Photos contributed by Mike Mansfield Museum, The University of Montana, Roger Siemens and Stu Hoefle

Questions always went through my mind as we approached and circled the fire: ‘How big is it? What’s the smoke look like? What kind of a jump spot will we have? Will I land in a tree again?

- ROGER SIEMENS

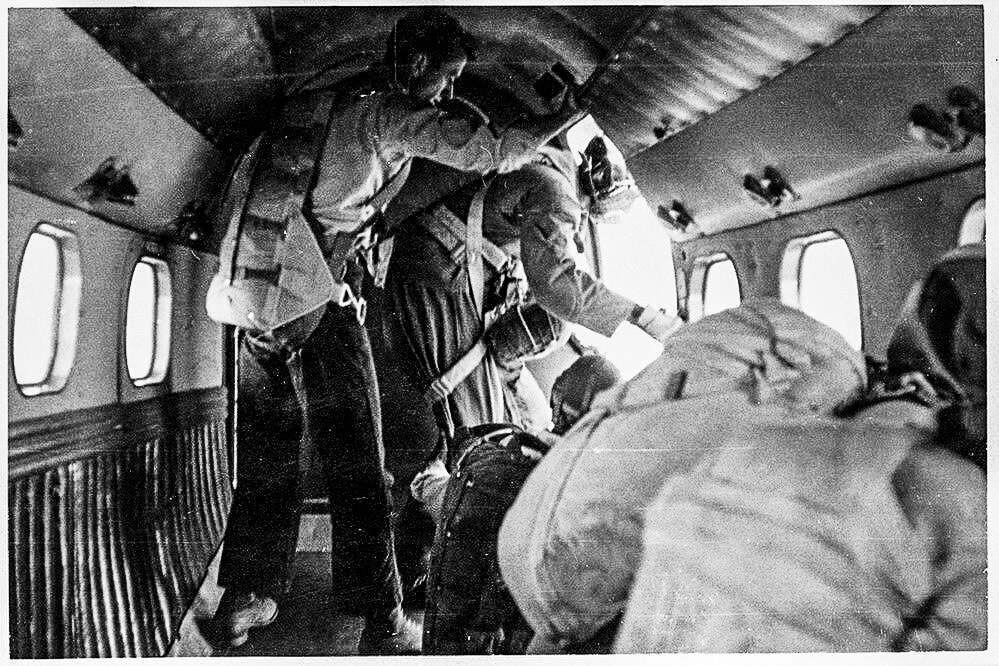

Roger Siemens crouched in the doorway of the DC-2 as the plane circled above the fire. He could hear the spotter and the pilot talking but, with the noise of the airplane, couldn’t make out what they were saying.

The spotter lay on the floor beside the men, watching closely out the door. As the plane leveled out, he cautiously checked the wind direction against the position of the plane and guided the pilot toward the intended drop zone. The men’s excitement grew. Roger and two other jumpers waited anxiously, in the door, for the signal to jump.

The summer had been unusually hot and dry, and a record drought spread across the state. Already the jumpers had been on more than a dozen fires across the region. This fire, though, would stretch the jumpers beyond anything they had imagined, would narrowly miss taking their lives and would remain the most memorable of their careers.

It was August 4, 1961. Roger was 22, and he and his wife, Rita, had a 2-month-old son, Rodney. On a rotating list of 30 jumpers, he knew he was close to the top and would be jumping again soon. He loved his job. Jumping out of planes and fighting fires lit a fire in him. With a degree in wildlife biology, Roger had yet to secure a job in the field, and being a jumper not only helped him support his family, it also fed his adventurous spirit.

The call came into the Missoula Smoke Jumper Base late in the morning. A small fire had been spotted on the Higgins Ridge, a remote, highly wooded area in the Nez Perce National Forest about 30 miles from Hamilton, south of Missoula. Already eight jumpers from Grangeville, Idaho, were on the fire, but with the perfect fire conditions for it to spread quickly, another 12 jumpers from Missoula were called in. It was believed that it was spotted early enough to be contained quickly. If all went well, it would be out in no time.

“We always got excited coming onto a fire,” Roger said, reflecting back. “We all loved jumping, so we were excited to be doing it again. Questions always went through my mind as we approached and circled the fire: ‘How big is it? What’s the smoke look like? What kind of a jump spot will we have? Will I land in a tree again?’ I remember we were all excited. We liked our jobs, and we were at it again.”

Soon the spotter signaled to jump, and Roger and two others vanished out the door, leaving the remaining nine to jump with each circling of the fire.

“There’s no hesitation,” Roger said. “The spotter will push you out if you do. They need to get us out of the plane and on the ground as quickly as possible.”

The drop zone was tight and crowded with mature trees, the forest thick from decades of growth. Roger hung up on a tree, which, he claims, was typical. He quickly rigged up a rope and lowered himself to the ground. Within minutes the remaining jumpers were also on the ground. The plane made one more pass, dropped to 400 feet and parachuted the firefighting gear down to them. The men scrambled to put their gear into their packs, leaving it in exchange for their tools and canteens. They took instructions from their fire boss and headed out to the edge of the fire.

The first crew in was on the east side of the ridge and Roger and his teammates were assigned to stay on the west side to try to contain the fire there.

Roger was using a new piece of equipment called a flail trencher. Much like a weed eater with a chain instead of line, it was powerful enough to break into the ground and make a foot wide trench. The fire conditions were extreme. Embers were drifting up over the line creating spot fires, but Roger was making progress.

“I’d been using the trencher,” he said, “when all of a sudden, the wind came up. A bad wind. It hadn’t been blowing at all, but it just came up and the fire took off.”

“There’s no hesitation. The spotter will push you out if you do. They need to get us out of the plane and on the ground as quickly as possible.”

A powerful weather front blew in, the wind hit the area and fueled a violent, swift-moving inferno that fanned the ridge with a roar. What looked to be containable just minutes before blew up. Trees were exploding, flames flew everywhere, visibility dropped, and temperatures soared.

The men were in trouble.

“We were in two groups,” Roger stated. “The eight guys and Ross, a squad leader, on the east side, I later found out, found a pile of rocks to lie down in to keep out of the path of the fire.”

Roger and his co-workers were being led by Fritz Wolfrum, an experienced fire boss. With more experience than Ross, Fritz became the Fire Boss for the fire once he landed. In a matter of minutes, Fritz ordered them to grab their canteens and a five-gallon container of water, wet themselves down and cover their faces with their bandannas.

“I didn’t think about anything but doing what my boss said to do,” Roger said. “He was yelling, ‘We gotta get outta here,’ and we followed him.”

Fritz boldly led the men into the fire instead of trying to outrun it. As the story has been told, from the plane Fritz had seen an area that had already been burned and made a mental note of it. He knew that if his men got in trouble, their best chance to survive would be to get to that location. His quick thinking was later credited with helping to save the lives of the 12-man smokejumper crew as they scrambled to get to the spot while the entire mountain side exploded in an inferno around them.

Wearing their standard firefighting uniforms, blue jeans and heavy boots, the jumpers were also sporting their newly assigned bright orange shirts. Treated to retard fire, they had just been brought into use by the Forest Service, and they helped protect the men as they fought their way through the fire.

“Fritz ordered us to dig away the ash and lay as flat a possible against the charred ground,” Roger continued. “It was so hot! We huddled there together. When I glanced up, I couldn’t see anything around me. The smoke was so thick, it was choking us. My throat hurt. My eyes burned. The hanky wasn’t doing a bit of good. We started losing oxygen. Some of the guys were throwing up and others were on the verge of passing out.”

Hemmed in with fire on all sides, the men huddled closely together. Miraculously the wind shifted and with it came the blessed oxygen of which the men had been deprived. But just as quickly the smoke would whip back in leaving the men prisoners as they waited for another miracle. Within hours the fire blew up from a couple of acres to almost 6,000. The conflagration was destroying everything in its path, fueled by 60 mph winds.

“I remember gasping for breath,” Roger continued. “But just when I thought it’d be the end of us, the wind would shift again, and we’d get a reprieve. I kept thinking about Mann Gulch and sure as heck didn’t want that to be the way our story ended too.”

As the men were struggling to stay alive, Rod Snider, an accomplished helicopter pilot with Johnson Flying Service out of Missoula, and Bill Magnuson, a Moose Creek Forest Service Ranger, were dispatched to look for them.

Piloting a Bell 47G-3 helicopter, fighting heavy smoke, excessive winds, extreme heat, and low visibility, the two men scouted for the jumpers until they were about out of fuel. Taking time to refuel at a nearby ranger station, they quickly got back in the air and resumed their search.

On the ground, things were getting worse. As the fire crept closer to the men, the air was so hot that clothing was catching on fire and the lids on the canteens were melting.

“It was terrifying,” Roger said. “At one point a couple of the guys jumped up and thought they’d try and out run it. Several of us grabbed them and held them down. Fritz was yelling at us all to stay put.”

With the odds stacked hugely against them, Snider and Magnuson continued to frantically search the fire for the men. Finally, spotting the orange shirts through the smoke and flames, they headed toward them. Snider circled and began to descend straight down through the heavy smoke and high wind.

“I credit both Fritz and Rod for saving our lives. They both risked their lives big time to save ours. I don’t think about what could have happened that day very often. I’m just grateful that someone up above was watching out for us.”

The noise of the fire prevented the jumpers from hearing the helicopter until it was within feet from their heads. Lowering the helicopter, Snider hovered over the side of the ridge. Magnuson jumped out and gave his place to two of the smokejumpers. Snider took off, deposited the men in a safe area and returned. As he headed back down, he put up four fingers, indicating that he wanted four guys this time. With not enough room inside the cockpit, two guys were told to lie on top of the cargo racks above the skids.

“I was one of those guys,” Roger continued. “There were no doors on the cockpit and Rod yelled out at me, ‘Hold on to your helmet, don’t let it fly into the rotors or we’re toast.’ I held it as tight as I could against my chest. It was my first helicopter ride. I’ll never forget it.”

A few minutes later, Snider placed the men in a safe area and immediately returned to the ridge to pick up more. Dangerously overloaded, he continued to lift the men to safety by fours until each man was safe. Fritz Wolfrum and Bill Magnuson were the last two men to evacuate.

Rod Snider was awarded the American Forest Service Medal for heroism and honored for saving the lives of all the men. He received “Pilot of the Year” from the Helicopter Association of America. He credited the Bell helicopter for saving the men against the odds of the wind, the heat and the cargo weight limit.

“I credit both Fritz and Rod for saving our lives,” Roger said. “They both risked their lives big time to save ours. I don’t think about what could have happened that day very often. I’m just grateful that someone up above was watching out for us.”

The close call at the Higgins Ridge Fire didn’t stop any of the jumpers from heading to the next fire. After being treated for smoke inhalation and minor burns, a week later most of them were back to jumping. Roger continued smoke jumping for five years before he began his 30-year career as a Forest Ranger.

Sixty years have passed since the Higgins Ridge Fire. All in their 80s, Roger Siemens and Rod Snider, along with several other survivors are being profiled for a documentary to be shown on Montana PBS next year.

As Roger reflected back on that unforgettable day, he ended by saying, “I didn’t even tell Rita about it right away. It was just another day on the fire line. A very memorable one!”